I Saw Peter Pan Fall Like Lightning From Heaven

And now I know the way

Once upon a school day during recess, the playground was empty.

Not a kid on a swing.

Not a kid hanging from the jungle gym.

And the soccer balls and basketballs lay still, forgotten.

Why didn’t the recess monitor notice and go seeking the lost children? Because this was a tiny religious school with zero money. We didn’t have a recess monitor. We had the recess honor system. Which is why all the children were completely missing.

Where were we?

At the far end of the playground, just inside the tree line, gathered at the top of a very steep bank, which fell away down into the deep inner darkness of the woods.

And we were jumping.

Jumping from the crown of the bank down into that dark.

The hill was a great one for jumping because it was forgiving, a hill covered in leaves, and beneath them stretched a baby-fat slab of loose earth.

We took turns jumping, landing six feet down the hill, ten feet, and then a massive leap brought one of us three quarters of the way down the hill.

That kid landed, rolled, and his roll delivered him to the bottom of the hill, down to the forest floor where the darkness had swallowed the dry bones of a thousand free beasts and digested them into a stew of legend fuel.

It is now important to know my best friend, Peter, was the one who did the three quarters jump.

In all things, he was the one of us who made the records, and we were the ones of us who lived within the boundaries of those records.

Only Peter was Peter enough to make and break the records.

Our Pan.

Because he was awesome.

By that, I mean crazy.

For the thirteen-year-old, there is no difference.

My friends, if you’ve never been best friends with Crazy, what are you waiting for? Crazy is unpredictable and doesn’t believe in pain or consequences, and these are the necessaries if you’re interested in living up to the wildness of your spirit, dang it.

And most importantly, Crazy knows where memory is hidden. It hides within the new, the dangerous, and the extreme. Everything else is predictable, safe, and repeated into the numb-nothing of infinity; it goes down smooth, without a single barb to hang it on the memory wall.

According to memory, a safe, predictable life is about ten years long, even if that life lasts a hundred years.

Without checking your diary, what did you do five days ago?

Exactly.

Crazy lives a long, long life as far as memory is concerned, even if Crazy dies young.

And it always does.

Now, let’s meet Peter The Crazy.

ONE

When teachers sent him to the principal’s office (and didn’t they all, and didn’t they always?), he did not go.

He haunted the hallway just outside the classroom door.

He reached in when the teacher wasn’t looking and made the lights flicker like machine gun fire. He reached in and picked up the American flag and waved it while we allies died in our attempts not to explode with joy and laughter.

TWO

Peter had been told about poison ivy, what it does. “Screw what it does,” said he. “This is what I do.”

He played a day away in a field of poison ivy and turned into a bloated, leaking, mutant boy who got to miss school for two weeks.

But he hobbled to school anyway just to show me his face, and out of his one eye, he saw my horror, and oh, how he loved it.

THREE

One day, Peter came to class without his book, notebook, or pencil. Naked, in other words. Mrs. Dennen headed his way and launched herself into the good fight.

Mrs. Dennen was a long-term sub. The school needed her because the previous teacher had been poached by a school that could pay with money. In came Dennen out of retirement to work for communion wafers and to be the oldest teacher and human being we’d ever seen.

She was small, she was mean, and she only loved one child: her grandson. She talked about him all the time. How good he was. How unlike us he was. We tried to push childhood diseases his way with our prayers.

Mrs. Dennen squared up in front of Peter The Great Crazy and said, “Where’s your book?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Go get it.”

“I said I don’t know where it is. How can I get it if I don’t know where it is?”

For a moment, Mrs. Dennen was stuck. Then she unstuck herself by saying something surprising:

“Peter,” she said, “I pray the peace of Jesus on you.”

I guess it wasn’t that surprising. After all, this was God School. It was surprising, however, that she was right:

Peter was not at peace.

He was a kid swarming with something like bees in the deep heart’s core, bee-sized flying pigs drunk on Legion. It’s what made him so wonderful. He couldn’t sit still, couldn’t follow rules, couldn’t stop chewing his arm off when he felt it shackled by some societal norm or natural law.

Yes, peace is probably what he needed.

But peace is not what he could ever accept when it was peace firing from the muzzle of Mrs. Dennen, peace wearing a full metal jacket of Jesus.

No sir.

So, as you know, Mrs. Dennen said, “I pray the peace of Jesus on you,” which prompted Peter to blow our minds by saying this:

“I don’t want it.”

You should have seen our faces. Nay, you should have felt our hearts. They pulsed once, hard, icily then not again. Neither did we breathe. We the many kids of that classroom were clinically dead while Mrs. Dennen blinked once and heavily then rallied with “But, Peter, I pray it on you.”

“Yeah,” said Peter, “and I don’t want it.”

Mrs. Dennen took it to the next level, caliber, decibel, etc. She shouted the peace of Jesus at Peter.

And Peter, our Crazy, our Pan, shouted right back:

“I DON’T WANT IT!”

You’ve felt our hearts, now see their faces:

Dennen and Peter leaned toward each other, the noses of their ghosts touching, their soul eyes pressing together, nearly bursting under the pressure and the power of the glory.

It must have become clear to Mrs. Dennon that Peter would not budge — his name was written on skipping stones in hell — so she said, “Go to the office.”

She didn’t have to say it twice.

Up jumped Peter and away he danced out the door.

11.1 minutes later, or 666 seconds, but probably way sooner, the consequences of Dennen’s good fight found the classroom:

Signs and wonders.

The door creaked open on its own, plenty wide enough for the passage of a ghost’s arm.

The lights flickered.

The stars and bars waved.

The children filled with memories they’d take to the grave.

On with the tale.

After Peter jumped and landed at the three-quarters mark and rolled all the way to the bottom of the hill, he spent some time on the forest floor. He lay gazing at the high ceiling of needles and leaves, looking into the million million needle points of sunlight straining through…

And he received his call.

His need to break open a bigger memory, a gift for all of us, a lengthening of life that would never dissolve, not even on the crushing floor of the deepest sea of time.

It was so dark down at the bottom of the hill (despite the sun’s needles) it was hard to see Peter. He blended well with the leaves and hearty legend stew.

Then he stirred.

Then he climbed.

It was like watching primordial man emerge from a bottomless genesis puddle of ooze and crawl his way into 1994.

Peter summited then passed between us.

Then, to our surprise, he walked away.

No one knew where he was going or why or how he could go. Peter leaving? When there was still more hill to conquer?

Never.

We wondered what had happened to him down in the dark. Had something scared him, changed him? Had his landing and roll stolen the crazy?

Was Peter our Peter no more?

We didn’t have to wait long for answers. At about thirty yards from us, Peter stopped walking away.

He stopped, turned around, and stared at us. Stared through us.

Then, in a blink, a flash, a twinkling of the eyes, he went from standing still and staring to running.

Teeth bared, eyes basically lidless, arms and legs swing-slashing the air to shreds.

We scattered, we fell, we leapt left and right like a mob parting for a Jesus sprinting to cast himself from the temple top and scream halleluiah all the way to hell.

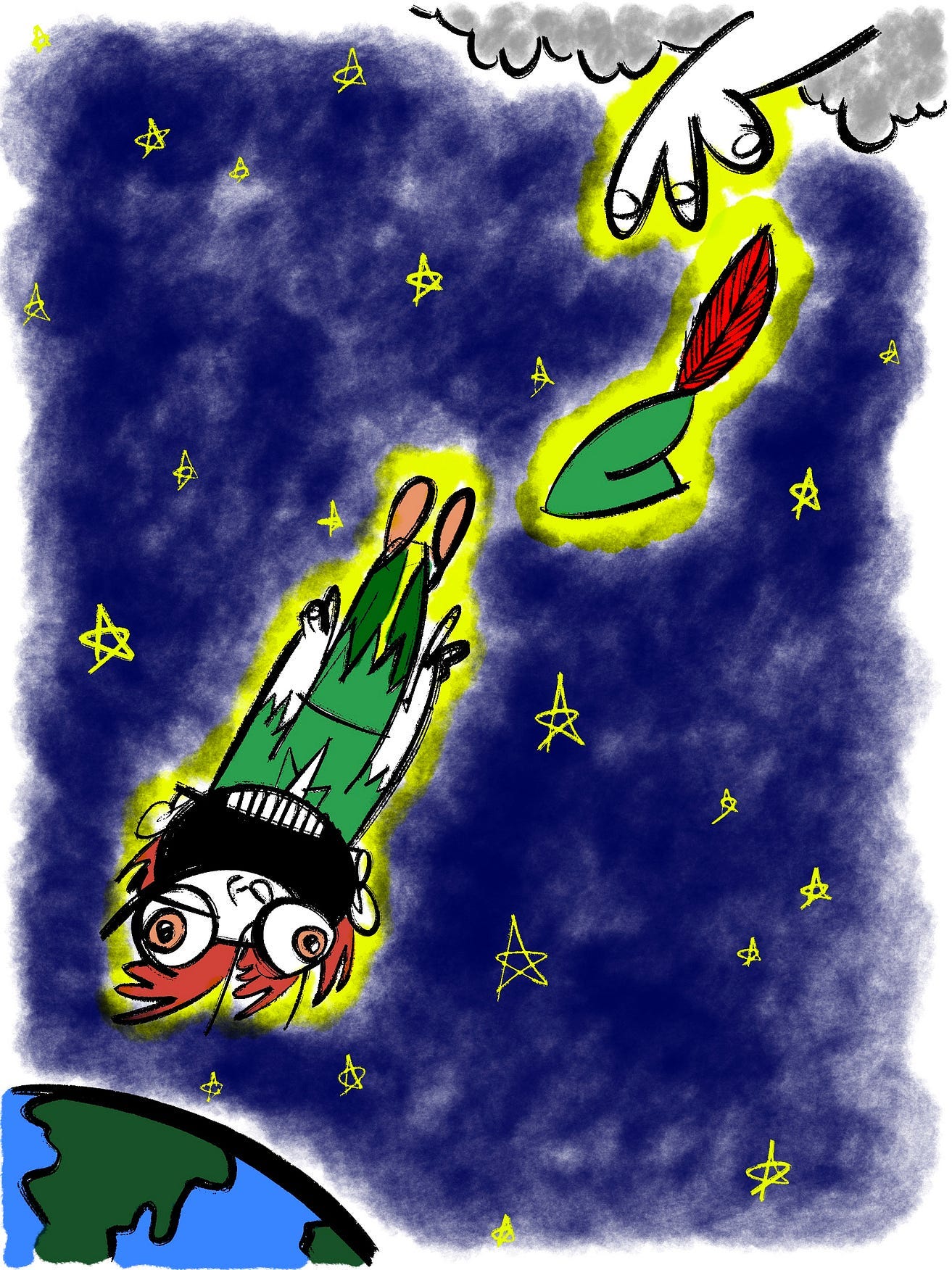

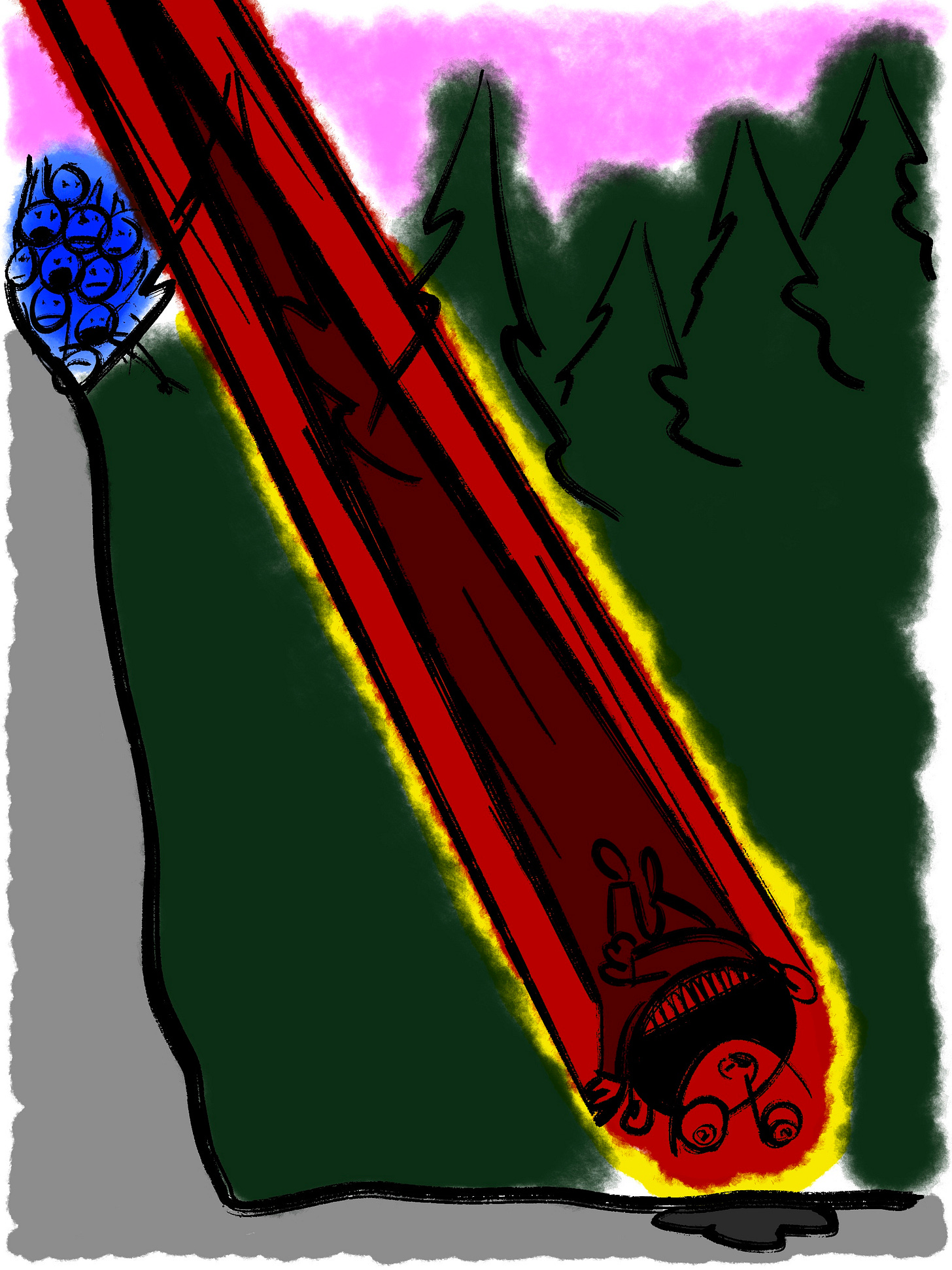

Peter blasted through the center of us then jumped from the top of the hill with all of his considerable might and madness.

Yes, he jumped.

He soared.

We watched our wild friend fly toward forever and into the midday twilight of the woods, higher up and higher out.

Those points of sunlight I mentioned, the shine-needles weeping through the canopy, intensified conveniently for this part of the story and speckled Peter’s flying body like the glowing snow-white sun dots on the coat of a summer fawn, halleluiah.

Also, the lights let him cast something of a shadow down onto the hill, a shadow that easily passed the six feet mark, then the ten, the three-quarters, and beyond.

And beyond again.

Until the shadow skated beneath him on the flat woods floor.

The distance from Peter to his shadow made it seem like he was leaving his shadow behind for good, severing himself from the world of solid things, becoming more than a wonderful boy, becoming a story, boy eternal, and no longer bound to bleed darkness in the face of the sun.

Be free, Peter! Stand tall and cast no shadow. You’re not the sun’s dial anymore.

We’ll see you on the other side of time.

Sadly, as you know already, Peter’s flight had to end. Right at the line which Einstein calls the “none shall pass,” Peter fell.

He fell straight for his cast-off shadow where it waited on the Earth below.

It waited there like an open mouth to gobble him up.

Peter fell fast and Peter fell hard, which is to say, badly.

After all, he hadn’t planned this part of his daring deed. He’d only planned to run fast and faster, jump harder, and fly farther than anyone ever before or again, and he’d achieved these things.

One and all.

But now he had to pay for them.

He paid by landing on his shadow like a meteorite of meat.

Peter’s body made an awful sound against the woods floor, the sound of a war hammer smashing Moses-cursed Egyptian watermelons — water into blood, if you follow me.

The landing knocked Peter’s wind out, every bit of it, and the wind ripped from his mouth a brief bark of a scream.

This sound didn’t comfort us. It did the opposite: It scared us so badly, we all lost our wind. We were a bellows of many nozzles, a bellows flat as ice, a bagpipe played by a boy with a boulder-sized spirit who fell like lightning out of heaven.

We rushed down the hill to our friend.

And we all saw it: a badly broken wrist. So badly. Puffy. A scary pink-purple. This wrist would later be set straight and wrapped in red — Peter demanded a blood-red cast. We coated it with the flesh of a thousand names, our own, some of us signing again and again, whatever Peter would allow — our way of getting a double/triple/quadruple portion of his spirit to be upon us.

But before the cast, before the bright hospital and its searing smells, we all gathered around fallen Peter in the darkness of the woods.

He writhed on the ground, making something of a leaf and pine needle angel there, and even while his breath was still long gone, he rasped out an order repeatedly, one we didn’t hear until finally a little wind came back into Peter’s flattened lungs, and the order was a word: “Sick.”

“Sick?” we said. “He’s gonna puke.”

He shook his head and said his word over and over until it was clearly not “sick” but “stick.”

And more than that, it was “Stick, stick, stick!”

I had no idea what this meant. Stick? What’s he mean, stick? None of us knew. But then one of us, I don’t remember who, decided not to figure out Peter’s riddle but to take “stick!” at face value: That kid found a stick and brought it to Peter.

Peter leaned up and opened his mouth wide, then he bit his teeth together twice, two clicks, and somehow the stick bearer knew what that meant.

The kid, Stick Boy, put the stick in Peter’s mouth, not like a cigar, but like a rose bitten by a tango dancer or a knife held in the teeth of a cliff-climbing pirate.

Peter bit down, giving us a great gift. We were seeing what no one sees anymore:

Medieval anesthesia live.

This made us grow up in a flash. After all, thirteen years old in the medieval season was middle aged.

In those woods with our growling, stick-eating patient; with nothing around us to say it was the 1990s and not the 990s; we got the eerie feeling that we were living outside of our time.

Outside of it, long before it, but we still carried our knowledge of the present, our familiar now, which, in the woods while standing by our fallen angel, felt like the distant future.

We knew so much that we could whisper in the dark, prophesy, things we were learning halfheartedly in school, things that felt like pure fantasy now: germ theory, antibiotics, and anesthesiologists.

Being ancient middle-aged folks and modern children all at once, we tasted of the heavy burden of living so long it’s eternal. And because of our vastness, we became wise, knowing what only the wise can know, that people (no matter who, no matter when) are people, creatures who live, desire life while living, and desire it so much that the wildest of them chase after life and living with all their speed and leap for it with all their strength.

And then they fall.

Always, they fall.

They land in darkness in the end.

But sometimes, before they go, they’re surrounded by friends, the ones who never forget them, the ones who befriended the new, the dangerous, and the extreme, and found that life could be so much more than safe, predictable, and numb. Nothing for the memory wall.

Life could be longer.

Long enough that it just might last.

For lots more, check out Misbehaving In Maine: 30 Half-Learned Lessons.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. You really nail that unsupervised exploration mode kids go into. Always finding the systems edge cases, arent we?